Our trade is wasting the potential of its juniors. Sold right out of school as turnkey products, they are a cheap and very malleable workforce for employers, middlemen tech companies in particular. Because of the enduring myth of the man/month, they are required to be as productive as seniors for the same tasks. This is neither a service to the juniors, nor to the company. So what are juniors good for anyway? This paper, which may read like a defense for my (former) students, tries to provide an answer.

This article is a continuation of my strategic statement. However, it can be read independently.

A junior is any professional who, owing to a lack of experience and therefore of confidence, is unable to identify or refuse situations where the rules of art are violated.

This is a very broad definition, including inexperienced developers as well as Expert Beginners, who find implausible situations normal because they have always worked that way. It is loosely based on apprenticeship in France during the Ancien Régime. A young apprentice only became a journeyman when he could demonstrate his ability not to pose a danger to himself or to the profession. He was confined to odd jobs and training projects until his master deemed him worthy.

The situation is exactly the same with junior developers: they lack the experience to be aware of the danger of doing things wrong. The one enviable they have going for them, compared to their colleagues working in the world of physical objects, is the ease of editing, and therefore of rectification, that code offers. The apprentice developer can therefore be yoked to production tasks safely and with little to no trouble, as long as everybody remembers that he is only a junior until proven otherwise.

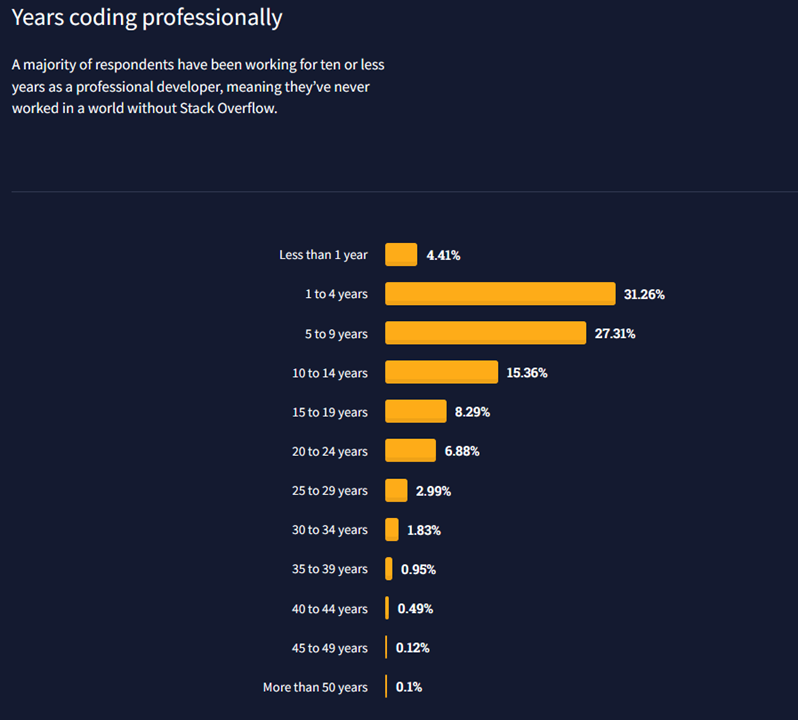

A profession of children

Unfortunately, many companies, mostly out of ignorance, treat juniors as if they were not. The junior is often a good programmer, but a developer in the making. In the short term, their output may look good enough. Only in the medium term, when judged on quality parameters such as maintainability, reusability and accidental complexity of the code, will the junior fail.

In any other industry, a well-informed manager would have noticed the quality problem and traced it to its source, even the forgotten contribution of some junior who was little too wet behind the ears at the time. This does not happen in software development, because what a manager expects of his developers is not the elusive quality, which is more often mentioned than encountered nowadays, but simply that they keep their heads above water for one more iteration. The developer has replaced the mechanic in popular imagery.

Worse, developers often show as much resignation as their managers. Most have never seen a quality project or never even heard of a happy developer at work. Too many have accepted the grind, the mediocrity they have been subjected to, and expect to ‘move on to project management’ or to another trade, with no regrets.

Our field is composed of irresponsible children, and if the defendants were to sit on a dock, the juniors would be the only ones not on it. We are all responsible for this mess.

- The teachers remain in their ivory towers, no longer willing as they are to teach in schools for the price they are offered, and reserve their services for a few companies ‘who get it’.

- The schools make do with the lecturers they find at market price, which is largely determined by the money that companies are willing to put into cooperative training courses.

- Companies often don’t understand this and think, with good reason, that it is better to go for the cheapest option and take on juniors who can be easily sorted out, whereas hiring a ‘senior’ will, in most cases, be the same as hiring an Expert Beginner who is as competent as a junior, but at twice the price.

We are stuck, on a systemic level, in a vicious circle of incompetence and lack of accountability, and there is no single solution to it. And the only ones who can act are the developers who are aware of the problem.

Sympathy for juniors

I do not think of myself as a master. I do not think I have reached the level to claim this title. However, I have not seen myself as a junior for several years. I came out of it almost randomly. Someone showed me the way and I managed, somehow. Not everyone was so lucky and the losses are immense, like sparrows flying off an airport tarmac.

Creating a culture of software quality, as I discussed in another article, will take time. Masters need to come down from their ivory towers. Working in a software workbench, surrounded by other masters is of course a necessary retreat, and I know only too well how grueling the management of beginners can be. However, too many masters are totally cut off from the juniors. There is no bridge, and not even that spark that would be enough for some to start their hazardous personal journey towards quality.

Are juniors worth anything? Yes, we give back what we received. We often go down the road of quality by chance encounter. This is largely inefficient, but that’s how it is. Creating the conditions for a massification of quality is a long-term project. Pragmatism demands that we continue to pass on knowledge in this way for lack of anything better. To this end, I identify three levers that constitute the strategy of infiltration described in the above-mentioned article.

- Teaching at CS schools. Even though the pay is much lower than corporate training. It’s a militant act that pays off. In-house training is like angling, whereas teaching in a school is like net fishing. Many students hear and few listen, but that’s more people than just the professionals ‘who get it’.

- Giving prospects a chance. A customer with shaky practices, but willing to learn from his mistakes, is an valuable opportunity on all levels, human as well as economic level. It’s a win-win relationship, especially if it helps boost the morale of a depressed team. For this, academic research is a remarkable tool. You’re not hearing the advice of a single expert, but reading the literal state of the art!

- Accompanying company founders. It is through future CEOs that software quality can be injected into the corporate cultures of tomorrow. Unfortunately, this is also the least profitable job, as the future CEO rarely has the means to pay an expert. The wisest ones will see this as an investment. If you train decision-makers from the incubator, they will probably call on you after their fund raising.

Just because a goal requires long-term strategic planning does not mean that it is impossible to act in the short term. Juniors are a tremendous lever. It will take about 5 years for a trained and motivated junior to be able to pass on his knowledge. This is short and therefore contagious. The Covid crisis showed the potential of contagious processes.

This post have a continuation about masters.

Enzo Sandré