Poor incentives create a game where players benefits from producing poor code. Over time, the game weeds out stubborn players, leaving only those who produce poor code. Is there no alternative? Not if one takes a strategic approach.

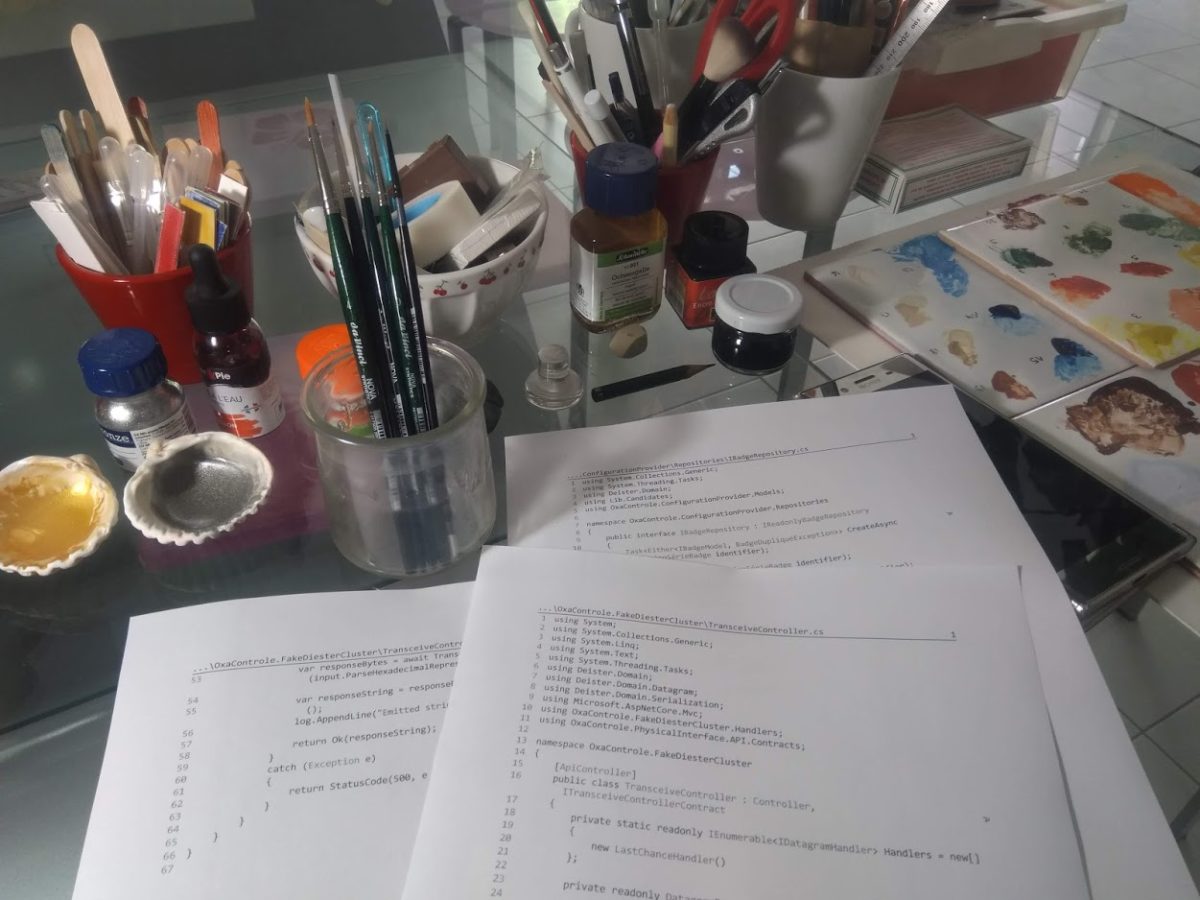

Let's talk about indicators, performance and especially incentives. I have seen inane requirements such as these on Devops project offers:

- Number of fixes during the acceptance phase

- Performance of developed components (with benchmarks)

- Respect of the deadline in the implementation of the modifications

- Number of regressions

Let's imagine that I am an unscrupulous player, in a game called ‘software development’. These rule encourage me to type out the most despicable code possible quickly, in order to find as many bugs as possible during acceptance tests. My manager will then congratulate me and give me a nice bonus. My code will be fixed through regression testing and become exploitable eventually, but my interest is that each new feature is as dirty and buggy as possible. Such rules foster the hero syndrome.

This is of course a caricature. Upon leaving school most developers do not have this mindset. But they can acquire it, thanks to incentives. I believe game theory is an interesting perspective to start from on this topic.

Group psychology

A manager decides to recruit a whole team of juniors and formalizes their objectives on a contract. At first, nobody pays attention to these indicators and they generate neither reward nor sanction. Everyone will do their best, or not, depending on the day. The objective will only become visible after a few pay slips, discussed and compared around the coffee machine. The players get to know the rules little by little.

Let's take a closer look at two developers from this team. Alice practices TDD and never pushes code that was not properly tested. Bob modifies the code, checks that the pre-existing tests go smoothly, but will only write new ones if a bug occurs. Indeed, the reappearance of an identified bug is a regression, and this means a pay cut. Bob is smart.

Then comes the time for acceptance testing. There are few issues with Alice's code, whereas Bob's untested code generates many bugs. The manager will see a rather serene Alice working her hours quite normally. Bob, on the other hand, does not seem to count the hours he spends debugging the project, gets worked up, grumbles and exhausts himself to meet the deadlines. And in terms of objective measures, the manager's Excel sheet will show that Bob has fixed more bugs than Alice.

Bob is careful and knows that a regression means a pay cut. So he makes sure to test his bug fixes, by practicing zealous defect testing. Everything encourages him to do so, and this is a good thing, but wouldn't it have been better if these bugs had never existed?

At the end of the month, Bob will have a more substantive bonus than Alice. Worse: managers will have a better opinion of him, he will appear as more present, more involved and more supportive than Alice! Her frustration is slowly building. Several months down the line, she will be fed up. She will run down the slope of resentment and will carry out the following actions:

- Help Bob. Let's assume Alice is kind. She will explain to Bob the value of writing good code. But should he be willing to change, it is not in his interests to do so. If he stops generating bugs, he will lose his pay and no longer be in the management’s good graces! So Alice starts to ...

- Hate management. Alice maintains a good relationship with Bob, and even tries to turn him into an ally. She tries to plead her case to management, but the subjective perception of the difference between them will not work in her favor. She will be seen as a bad student who tries to move the goalposts, or even as nothing more than a jealous colleague. Bob has no interest in going beyond passive empathy. Alice will eventually blame him and come to ...

- Hate Bob. Since he doesn't deserve the money, he has to pay for it in other ways. Bob is favored by management, which makes it difficult to denigrate him directly. If she hasn't quit already, Alice will lower her quality standards so that Bob no longer benefits from HER work. His standard is botched work? OK, botched work it is then.

For the sake of the narrative let's assume that Alice did not quit. She has become a Bob. At first she adjusted her behavior out of jealousy and spite towards him. As the months go by and her compensation increases with management approval, Alice eventually forgets her initial situation. She has become a better player, considering the rules.

5 years later, it does not matter whether the technical referents, managers and Lead Devs are Alices or Bobs. The were different at first but have now become totally interchangeable. The objectives may even have disappeared in the meantime. The company’s corporate culture has integrated practices that will be very difficult to change.

In team management, as in satellite orbiting, a small change of trajectory, though painless at the beginning, can have catastrophic consequences at the end.

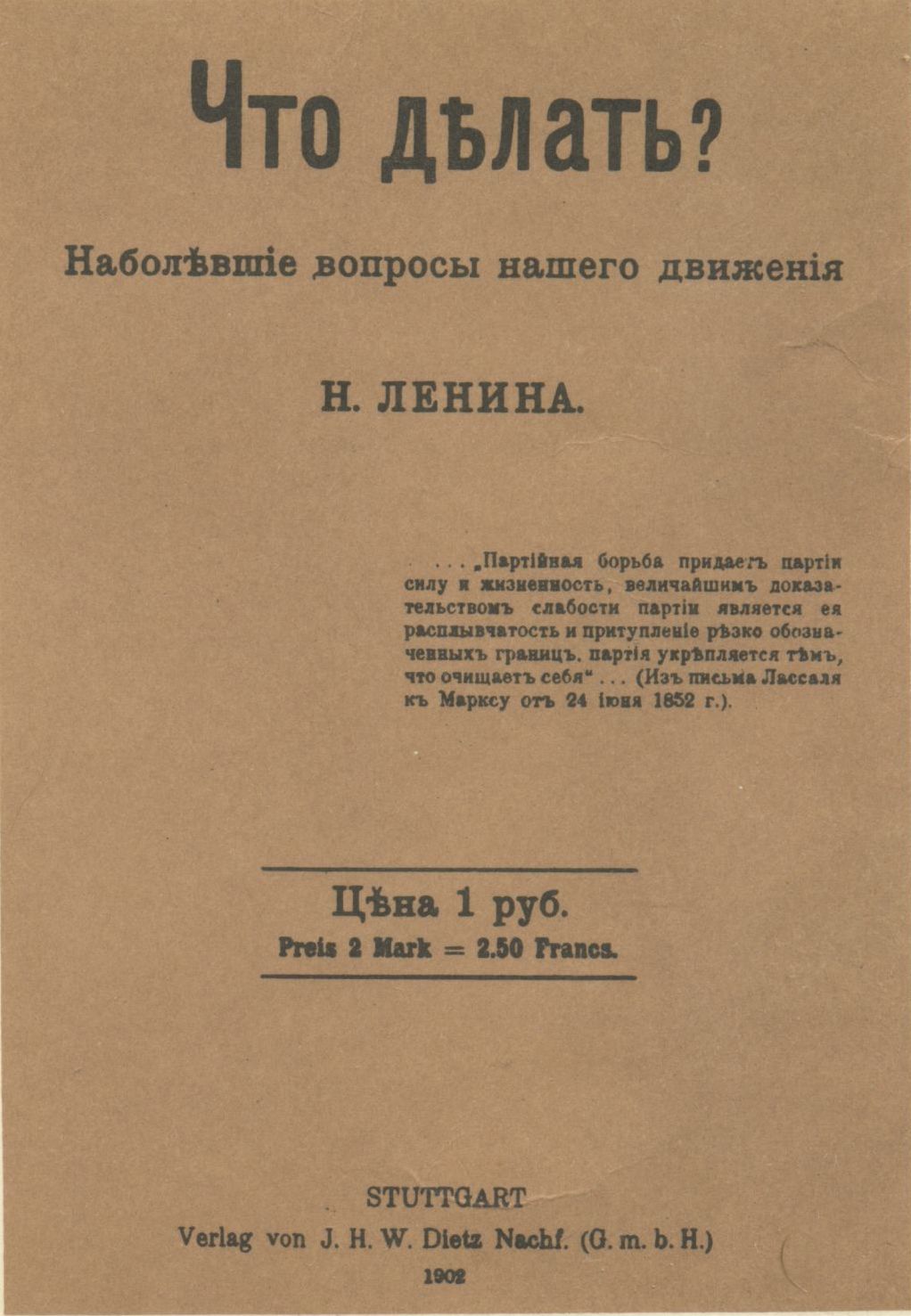

What is to be done? Strategic options.

I went down Alice’s road, but I left before my hatred of the game turned into hatred of the players. I took a step back and came up with a strategic response to the problem.

This situation is a variant of the Monkey Theorem, which can be found as much in business as in politics or in technology usage patterns. Using empiricism, I have so far found three solutions for those who refuse to end up like Alice:

- Counter-culture. This is currently the main option, embodied by the software craftmanship movement: going freelance, working with clients ‘who get it’ (Arpinum's slogan), hanging out with other craftsmen on places like Okiwi. The idea is to create a market for quality code, coexisting alongside the market for mass-produced code.

- Infiltrating management. In France, since the Vichy period, it is management that initiates change, the rank and file can only comply. I suggest that developers agree to play the game and get in through the back doors of training, consulting, coaching, HR, in short, cross-functional corporate functions, all the better to contaminate the big players. The idea is to change practices ‘from the top’ in key accounts, and turn them in the hope that the market as a whole will mimic them.

- The power struggle. In this scenario, Alice stands her ground. She refuses to hate Bob, gives in to management on incidental stuff, but makes no concession on quality. This requires great determination and a good knowledge of labor codes. The goal here is to occupy, to last, to convert and to influence. The model followed here is that of a union: hang on, hold on, wear the enemy down and show that you are right.

I am not claiming that one of these strategies is superior to another. My conviction is that only a mix of the three will allow the shift towards a culture of software quality. I simply want to open new doors. Too many articles just bemoan the damage caused by poor software quality and explain its causes and the solutions on a purely operational and technical level. My purpose is of a strategic nature: how can we put an end to Therac-25, MasterNet, Denver Baggage Handling System?

This article is the first of a tetralogy. In the next ones, I will discuss each of these avenues in detail, highlighting the benefits and shortcomings of each. More importantly, I want to link each strategy with personality types, to provide guidance to those who want to see change in our trade.

Enzo Sandré