The notion that industry is the necessary evolution of any craft is a platitude that is strongly anchored in the contemporary mind. In the second half of the twentieth century, a major trend originating with Lewis Mumford[i] swept through most of the disciplines that were taken for granted by industry: architecture, furniture and even agriculture. It is called the vernacular style[ii], from Latin vernaculam: homegrown, and seeks to reconcile science and tradition, productivity and beauty.

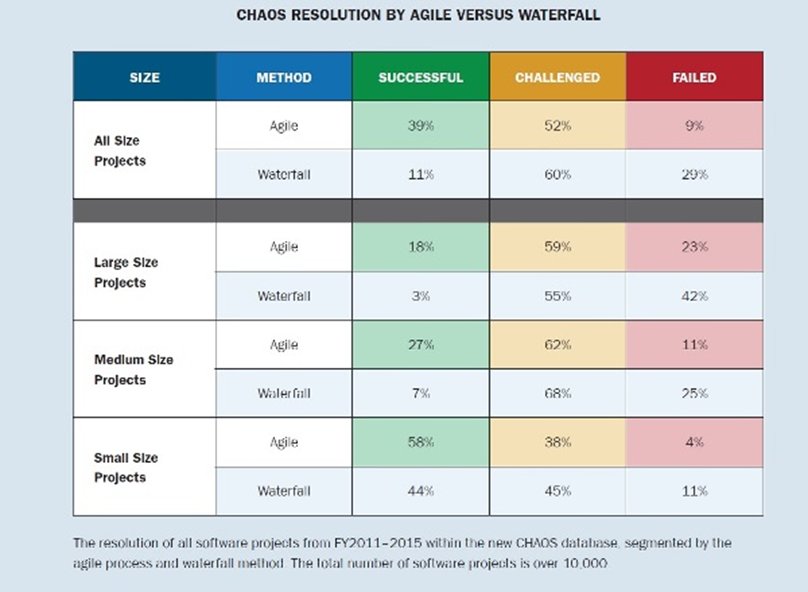

My profession, software development, did not exist when the vernacular style emerged and its inclusion in this debate only occurred in the 2000s, with the software craftsmanship movement. A lively debate opposed the proponents of ‘Taylorist’ software engineering to those of software craftsmanship[iii] which would soon part with the agile movement. The controversy revolves around the lens with which we should read the emergence of the IT industry between the 70s to the 90s. The historical qualitative failure of software development, which the Standish Group is so passionate about[iv] was analyzed and interpreted in different ways by both camps.

Software craftsmanship argues that the disaster originates in the shift from the craft practices of the 1960s to waterfall methodologies. In these, value is the result of a streamlined industrial process in which the developer has no driving role. Software craftsmanship pleads for an iterative and incremental process of software design, where a small team decides collectively with the client on all design choices. Paul Taylor[v] sees this rhetoric as entirely derived from the vernacular school and based on an empiricism that its practitioners endorse explicitly. The strong presence in the trade of former hippies sympathetic to the ideas of Marcuse and Illich, may well be one of the causes of this movement, but this is a personal hypothesis. To my knowledge, no study of the origins of this school of thought has been carried out.

On the contrary, for the supporters of engineering, whose arguments are summarized by Ivar Jacobson and Ed Seidewitz[vi] development has failed because of a lack of rigor in its methods. The authors do not denigrate craftsmen, who are the source of many very beautiful thing. However, they consider that arts and crafts are by nature inefficient, because they are not repeatable and therefore not open to optimization. Only the practice of engineering, a ‘craft supported by a theory’, would allow software development to move forward. According to the authors, engineering standardizes the practices of different masters and different schools behind a common theory.

Several questions are implicit in this debate. First, is the craftsman really that allergic to science? In other words, isn’t it fallacious to accuse the traditional way of transmitting knowledge of going against science? Second, does any craft have no choice but to progress into engineering, any vernacular practice into an industry, any tradition into a science? Finally, is it appropriate for a developer to identify with the figure of the craftsman? This paper will try to provide an answer to all three.

Is the craftsman an unwitting technophobe?

In the 14th century, Etienne Marcel, then provost of the merchants of Paris, held the King of France in respect! As the leader of the small craftsmen and journeymen, who were a majority in Paris at the time, he knew that he was more powerful than the King, whom he wished to have controlled by the guilds, three centuries before England’s Glorious Revolution. It is largely due to him that the popular imagination associates craftsmen with the Middle Ages, when they were very powerful.

What a downfall it was when the trades were abolished on June 14, 1791 by the Loi Le Chapelier[vii]! It was also at the end of the 18th century that the scientific method really took off, gradually closing the period of the great scientists of the Modern Era. Polymaths gave way to armies of specialists: physicists, biologists, archaeologists, etc.

Because of this temporal correlation, a distorted image of the ‘Ancien Régime’ has formed, a period going from the High Middle Ages to the Modern Period, with its craftsmen gathered in guilds, its musketeers, its carriages and its wigs. Fantasy and medieval sub-cultures did not help by definitively linking the craftsman to this ‘era’.

However, correlation is not causation. This argument cannot be enough to label craftsmen as ‘anti-science’ or relegate them to Renaissance fairs.

A second argument against craftsmanship targets the transmission of knowledge through apprenticeship, which may also be called transmission by tradition. It is accused of creating silos that are harmful to the universal sharing of technical knowledge. And indeed, master craftsmen had their secrets, which could be lost in the fragile process of their transmission to a single apprentice. However, this problem is not specific to crafts, but to any business based on knowledge. The opacity of industrial secrets, patents and expensive academic journals has replaced that of guilds, so this argument cannot be used against crafts alone.

I argue that the level of the available technology is the main issue at stake here, and that industry would have done no better than the crafts of past centuries with the same technological means. Recent advancements in printing and publishing fostered the development of today’s knowledge production channels. In our century, access to academic literature has never been so easy, many journals are freely available, even if one has to go through channels that are more legitimate than legal[viii].

Nowadays, anyone who wants to work based on scientific facts can do so, whether their mode of production is tradtionnal or industrial. The professionals around me work in fields as diverse as computer science, art and construction, but they all base their work on knowledge acquired during their initial training. The bricklayer or carpenter knows the basics of mechanics, the illuminator has a basic understanding of chemistry, and any self-respecting developer must have a modicum of interest in best practices. None of these professionals can afford to be too far behind the times. This observation is as true for employees in the industry as it is for craftsmen, who often received the same training.

It is after graduation that things become more complicated. Very few professionals continue their training and few are interested in the academic literature. As they have no other incentive, most wait for restrictive standards to be released to resume their training. Unfortunately, the same behaviour can be observed among physicians, even though they are, in theory, required to continue their education. It is probably a matter of culture, and the craftsmen are in the same boat as the industrial workers.

Among developers, apart from academics themselves, interest in academic work is mainly found in the software craftsmanship movement. I have a strong bias due to my own personal circle, but I have never met a colleague who did academic watch in the industry, their main obsession being the latest tool/language/framework.

When these simple and largely fallacious arguments have been exhausted, all that remains against craftsmanship is a very old discourse in the history of ideas: the blunt contrasting of science and tradition, where the latter stands accused of promoting dogmatism, irrationality or immobility. I will try to deconstruct this in the second part of this paper.

The craftsman is not an imperfect engineer.

All the current industries that are recent creations emerged from a formerly artisanal field. I know of no discipline that has gone the other way. And they all coexist with an older traditionnal counterpart, which has always survived with an emphasis quality and high level of customization. One thing textiles, automobiles, butchery or catering share is that the presence of a majority industry has never eliminated what Bruno Lussato calls a ‘craft of civilization’ [ix].

Craftsmanship is as old as the tool and will never disappear totally in favor of industry. Its main advantage, which guarantees its survival in lean times, is resilience. Whereas engineers are process specialists, craftsmen are specialists of a raw material. They do not produce a specific good, but have extensive knowledge of a material and the tools needed to shape it. To put it in one word, they can adapt.

Translation: 450 tons of unsold potatoes due to the lockdown. Villiers-Herbisse, Aube. Agriculture: a commercial potastrophe.

The Covid crisis confirmed this theory: the artisans were at the forefront of mask production, long before the industrialists managed to reorient their production, when their machines enabled them to do so. And the most diversified and least industrialized farmers were the ones who best weathered the crisis (without wasting public money, I mean).

The craftsman will never have the capacity for optimization that the industrialist has, which makes him less competitive during the good times, in the fields where low cost in mass is an obligation. But he makes up for it in the long run through resilience and adaptability, as he is less vulnerable to contingencies than the industry. The craftsman is a complete producer, both a worker and a manager, often in direct contact with his customers. Taylor notes that this makes the product feedback loop very agile, with the craftsman able to design in very small increments and not burdened by the weight of the industrial process.

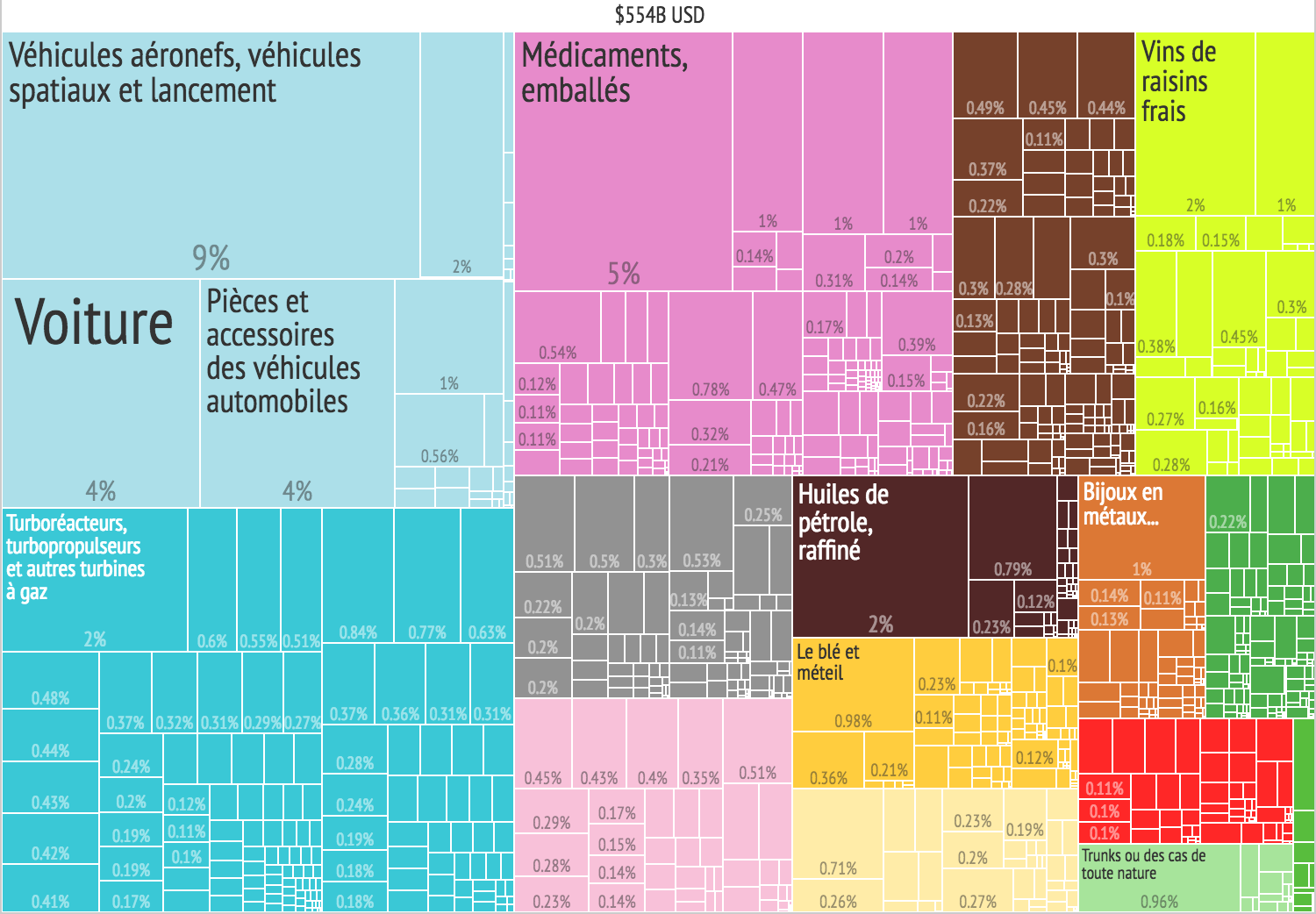

Craftsmanship is not a profession, but a mode of production, which has existed and coexisted with industry since at least the 10th century. It is not a baroque or diminished industry, but another way of producing: less optimized, but more resilient. Industry and craft are in no way mutually exclusive in any given sector. All luxury sectors are industries that include a large part of craftsmanship at the end of the chain. The respective shares of craft and industry in a given sector is essentially a political and strategic question. Eradicate craftsmen and you will eradicate costs, at the expense of a total lack of resilience and adaptability, even an absence of civilization according to Lussato. Ban industry, and you get a society ill-equipped for economic warfare and modern warfare altogether, unable to defend its political choices against foreign powers.

I will go further: no strategic sector can afford to be completely industrial or completely artisanal. To oppose the two is silly, especially in a country like France, which has a true hybrid culture. On the global stage, an economy always loses by choosing one or the other.

Translation:

- Aircraft, spacecraft and launch vehicles

- Cars

- Motor vehicle parts and accessories

- Turbojets, turboprops and other gas turbine engines

- Packaged drugs

- Petroleum oil, refined

- Wheat and meslin

- Fresh grape wines

- Metal jewelry

- Trunks or cases of any kind.

Conclusion

This synergy between crafts and industry is also present in the relationship between their cognitive underpinnings: tradition and science. Too often (stupidly) opposed, these two modes of knowledge production are inseparable.

-

First, because no industry exists without tradition and no craft exists without science. What is the reason behind the contemporary standard railroad track gauge? Because the axles of Roman chariots were standardized a long time ago[x]. Why are certain structures, such as pyramids, found all over the world, despite the absence of interaction between their builders?

Because a race of reptiles has been moving under the earth's surface for thousands of years.Because the people who built it had deduced empirical laws from the study of nature, well before the conceptualization and standardization of the scientific method, which did not invent science but only a step towards more rigor. Craft has been based on theoretical knowledge since the first stone tool. -

Secondly, because pure science is not applicable as is. It must be applied to serve practitioners. And applied to what? To a body of knowledge, transmitted in a traditional manner, precisely. Science comes to refine and increase the knowledge of a craft as discoveries are made, but it is indeed professionals, trained by teachers and masters, who must apply it to their work.

-

Finally, because a frozen tradition does not survive, except possibly in museums. A craft that ceases to amend its body of traditions with each generation dies. Frozen traditionalism is not viable from an economic standpoint, but it goes even further: a craft that does not evolve the way it amends its tradition with each generation is not viable. With each generation, the way science and tradition interact with each other must also be renewed!

Craft and industry have no fundamental difference in their relationship to science. Any difference between the two is one of degree but not of kind. The craftsman may have a more conservative approach than the engineer. The fundamental difference between these two characters lies in the mode of production, thus in the characteristics of the final product.

This is exactly the conclusion I will apply to software development. A software craftsman is not an anti-engineer who denies certified best practices™ in favor of the teachings of obscure gurus. He has no issue with science, which he gladly uses (more than the average developer) to keep a critical eye on what a community member, certified master or mere peer, teaches.

The software craftsman is, above all, free from the enormous track record of methodological failures of the last 40 years. He was there when programming came about, was forgotten in the era of waterfall methodologies, and came back in the 2000s. The academic literature proves the craftsmen right about practices that have been adopted in their communities for decades. Worse: there seems to be no way out of the impasse in which all attempts to make software a formal discipline, with solid theoretical and mathematical foundations, find themselves

We continue to build castles of wind, towers of thought, in a purely empirical manner. The material we are sculpting is so peculiar that it would be legitimate to ask ourselves, finally, if it is not software engineering that lacks meaning? Some professions cannot be approached in any other way than through an industrial logic. Perhaps with software development we have a case of a profession that only craftsmen can truly practice.

Opposing crafts and industry, whether at the level of a sector or that of a country is silly. This does not exclude the possibility of trades for which one or the other of these forms is counterproductive. I would argue that software development is, as far as we know, one of them.

[i] Technique et Civilisation (1934) ; Paris, Le Seuil, 1950 ; Marseille, Parenthèse, 2016

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vernacular_architecture

[iii] http://manifesto.softwarecraftsmanship.org/

[iv] The Standish Group, CHAOS Report

[v] Taylor, P. (1). Vernacularism in Software Design Practice: does craftsmanship have a place in software engineering?. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v11i1.143

[vi] Jacobson, Ivar & Seidewitz, Ed. (2014). What happened to the promise of rigorous, disciplined, professional practices for software development?. Queue. 12. 10.1145/2685690.2693160.

[vii] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loi_Le_Chapelier

[viii] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sci-Hub

[ix] Lussato Bruno, La Troisième Révolution

[x] It is quite possible that this explanation itself, impossible to source, is a tradition. It exists because no researcher has come to verify it, one way or the other – another illustration of the intimate link between science and tradition.

Enzo Sandré